What is an API

There are millions of APIs online which provide access to data. Websites like Reddit, Twitter, and Facebook all offer certain data through their APIs.

To use an API, you make a request to a remote web server, and retrieve the data you need.

But why use an API instead of a static CSV dataset you can download from the web? APIs are useful in the following cases:

- The data is changing quickly. An example of this is stock price data. It doesn’t really make sense to regenerate a dataset and download it every minute — this will take a lot of bandwidth, and be pretty slow.

- You want a small piece of a much larger set of data. Reddit comments are one example. What if you want to just pull your own comments on Reddit? It doesn’t make much sense to download the entire Reddit database, then filter just your own comments.

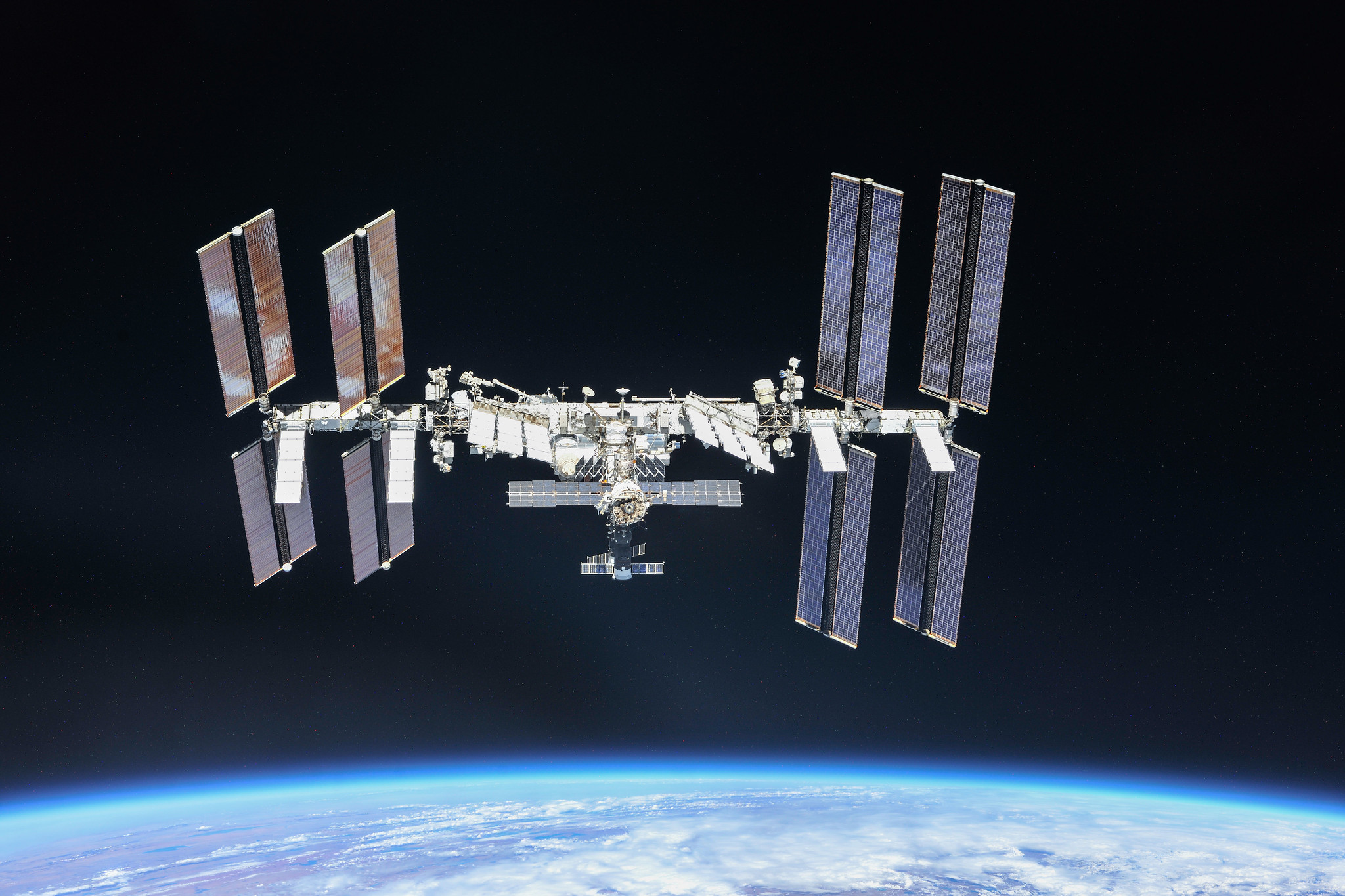

- There is repeated computation involved. Spotify has an API that can tell you the genre of a piece of music. You could theoretically create your own classifier, and use it to compute music categories, but you’ll never have as much data as Spotify does. In cases like the ones above, an API is the right solution. We’ll be querying a simple API to retrieve data about the International Space Station (ISS).

An API, or Application Programming Interface, is a server that you can use to retrieve and send data to using code. APIs are most commonly used to retrieve data, and that will be the focus of this beginner tutorial.

When we want to receive data from an API, we need to make a request. Requests are used all over the web. For instance, when you visit any page, your web browser made a request to the web server, which responded with the contents of web page.

In order to work with APIs in Python, we need tools that will make those requests. In Python, the most common library for making requests and working with APIs is the requests library. The requests library isn’t part of the standard Python library, so you’ll need to install it to get started.

If you use pip to manage your Python packages, you can install requests using the following command:

pip install requests

| |

Now that we’ve installed and imported the requests library, let’s start using it.

There are many different types of requests. The most commonly used one, a GET request, is used to retrieve data. Because we’ll just be working with retrieving data, our focus will be on making ‘get’ requests.

When we make a request, the response from the API comes with a response code which tells us whether our request was successful. Response codes are important because they immediately tell us if something went wrong.

To make a ‘GET’ request, we’ll use the requests.get() function, which requires one argument — the URL we want to make the request to. We’ll start by making a request to an API endpoint that doesn’t exist, so we can see what that response code looks like.

response = requests.get("https://api.open-notify.org/astros1.json")The get() function returns a response object. We can use the response.status_code attribute to receive the status code for our request:

print(response.status_code)404Let’s learn a little more about common status codes.

API Status Codes Status codes are returned with every request that is made to a web server. Status codes indicate information about what happened with a request. Here are some codes that are relevant to GET requests:

- 200: Everything went okay, and the result has been returned (if any).

- 301: The server is redirecting you to a different endpoint. This can happen when a company switches domain names, or an endpoint name is changed.

- 400: The server thinks you made a bad request. This can happen when you don’t send along the right data, among other things.

- 401: The server thinks you’re not authenticated. Many APIs require login ccredentials, so this happens when you don’t send the right credentials to access an API.

- 403: The resource you’re trying to access is forbidden: you don’t have the right perlessons to see it.

- 404: The resource you tried to access wasn’t found on the server.

- 503: The server is not ready to handle the request. You might notice that all of the status codes that begin with a ‘4’ indicate some sort of error. The first number of status codes indicate their categorization. This is useful — you can know that if your status code starts with a ‘2’ it was successful and if it starts with a ‘4’ or ‘5’ there was an error. If you’re interested you can read more about status codes here.

In order to ensure we make a successful request, when we work with APIs it’s important to consult the documentation. Documentation can seem scary at first, but as you use documentation more and more you’ll find it gets easier.

We’ll be working with the Open Notify API, which gives access to data about the international space station. It’s a great API for learning because it has a very simple design, and doesn’t require authentication. We’ll teach you how to use an API that requires authentication in a later post.

Often there will be multiple APIs available on a particular server. Each of these APIs are commonly called endpoints. The first endpoint we’ll use is http://api.open-notify.org/astros.json, which returns data about astronauts currently in space.

If you click the link above to look at the documentation for this endpoint, you’ll see that it says This API takes no inputs. This makes it a simple API for us to get started with. We’ll start by making a GET request to the endpoint using the requests library:

response = requests.get("https://api.open-notify.org/astros.json")

print(response.status_code)200We received a ‘200’ code which tells us our request was successful. The documentation tells us that the API response we’ll get is in JSON format. In the next section we’ll learn about JSON, but first let’s use the response.json() method to see the data we received back from the API:

print(response.json()){'message': 'success', 'people': [{'name': 'Alexey Ovchinin', 'craft': 'ISS'}, {'name': 'Nick Hague', 'craft': 'ISS'}, {'name': 'Christina Koch', 'craft': 'ISS'}, {'name': 'Alexander Skvortsov', 'craft': 'ISS'}, {'name': 'Luca Parmitano', 'craft': 'ISS'}, {'name': 'Andrew Morgan', 'craft': 'ISS'}], 'number': 6}JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is the language of APIs. JSON is a way to encode data structures that ensures that they are easily readable by machines. JSON is the primary format in which data is passed back and forth to APIs, and most API servers will send their responses in JSON format.

We need to import json by adding:

| |

You might have noticed that the JSON output we received from the API looked like it contained Python dictionaries, lists, strings and integers. You can think of JSON as being a combination of these objects represented as strings. Let’s look at a simple example:

The json library has two main functions:

- json.dumps() — Takes in a Python object, and converts (dumps) it to a string.

- json.loads() — Takes a JSON string, and converts (loads) it to a Python object. The dumps() function is particularly useful as we can use it to print a formatted string which makes it easier to understand the JSON output, like in the diagram we saw above:

| |

200

{'people': [{'craft': 'ISS', 'name': 'Mark Vande Hei'}, {'craft': 'ISS', 'name': 'Pyotr Dubrov'}, {'craft': 'ISS', 'name': 'Anton Shkaplerov'}, {'craft': 'Shenzhou 13', 'name': 'Zhai Zhigang'}, {'craft': 'Shenzhou 13', 'name': 'Wang Yaping'}, {'craft': 'Shenzhou 13', 'name': 'Ye Guangfu'}, {'craft': 'ISS', 'name': 'Raja Chari'}, {'craft': 'ISS', 'name': 'Tom Marshburn'}, {'craft': 'ISS', 'name': 'Kayla Barron'}, {'craft': 'ISS', 'name': 'Matthias Maurer'}], 'message': 'success', 'number': 10}

{

"message": "success",

"number": 10,

"people": [

{

"craft": "ISS",

"name": "Mark Vande Hei"

},

{

"craft": "ISS",

"name": "Pyotr Dubrov"

},

{

"craft": "ISS",

"name": "Anton Shkaplerov"

},

{

"craft": "Shenzhou 13",

"name": "Zhai Zhigang"

},

{

"craft": "Shenzhou 13",

"name": "Wang Yaping"

},

{

"craft": "Shenzhou 13",

"name": "Ye Guangfu"

},

{

"craft": "ISS",

"name": "Raja Chari"

},

{

"craft": "ISS",

"name": "Tom Marshburn"

},

{

"craft": "ISS",

"name": "Kayla Barron"

},

{

"craft": "ISS",

"name": "Matthias Maurer"

}

]

}Immediately we can understand the structure of the data more easily – we can see that their are ten people currently in space, with their names existing as dictionaries inside a list.

If we compare this to the documentation for the endpoint we’ll see that this matches the specified output for the endpoint.