Storing information

3 minute read

We’re going to understand how computers work by understanding a particularly common task from the 20th century that has been almost completely automated by computers: filing information.

A local library

If you visit your local school or neighbourhood library, it probably looks something like this:

This is a library which probably has a few thousand books. In a library like this, you will probably find it easy enough to find a new book to read simply by heading over to the appropriate section and wandering down the aisle until you come across something that interests you. But if you are looking for something in particular, or if you are looking for books about something, rather than by someone, you might look in the catalogue.

A bigger library

If you are at a university library, a major city library, or a national library, you might well be greeted with a view more like this:

This is a typical view in a university library: floor to ceiling books stretching for great distances in both directions. There could be a hundred aisles like this in a university library. This photo is from the University of Adelaide’s main library, the Barr Smith Library, which has over a million items in its collection. In a library this size, if you want to find anything you have to look in the catalogue.

Catalogues before computers

Before the 1990s, “looking in the catalogue” of a library didn’t involve a computer. Instead, you would find a card which had the information about the book you were looking for:

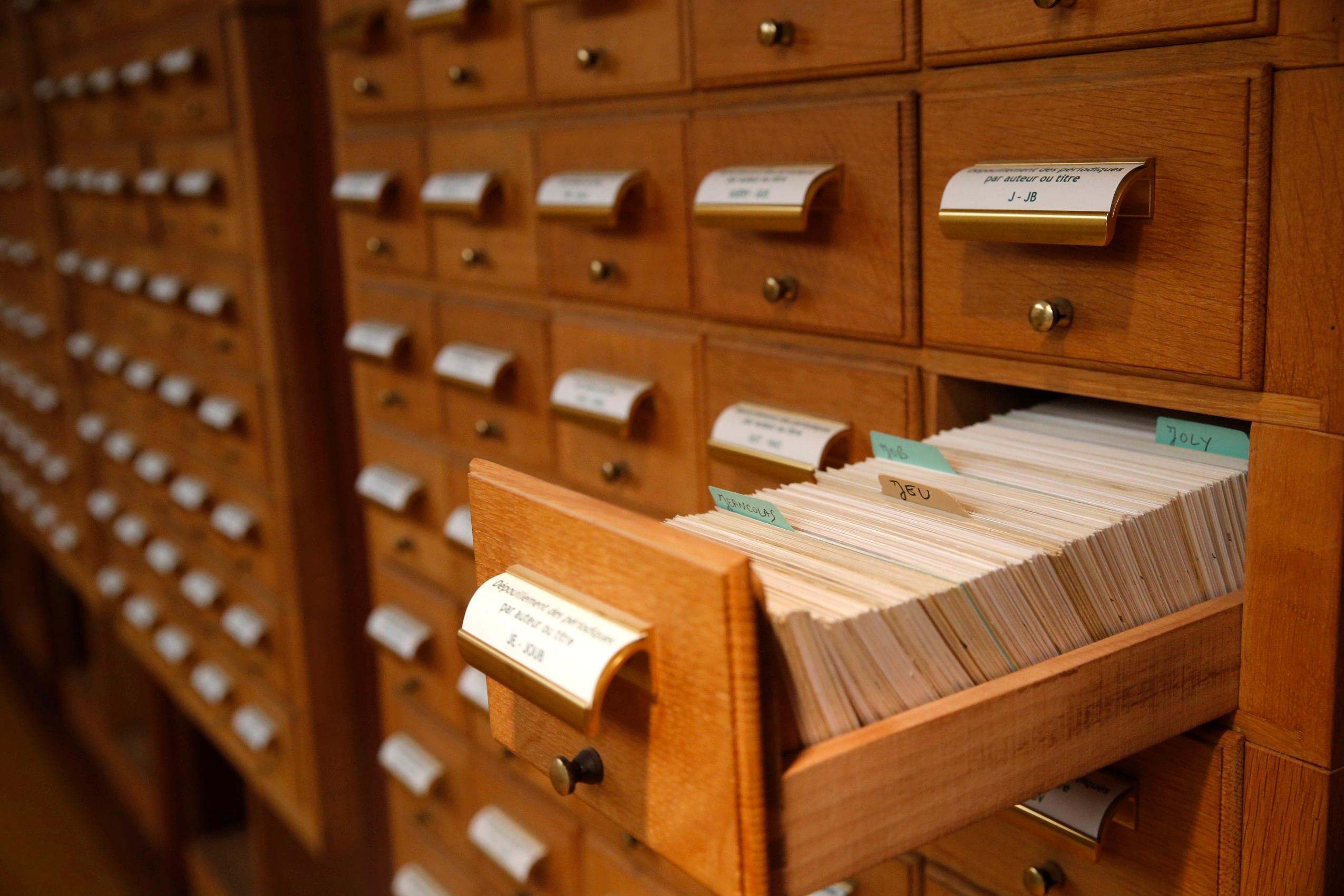

It would tell you the title, author, subject, often a brief description or the opening line of the item and, most importantly, where it was located. Cards might be hand-written or typed using a typewriter, depending on how old they were. Every time a book or other item was added to the collection, someone made up a card for the book and added it to the catalogue. The cards were organised in drawers, with a label on each drawer showing what was inside:

There would be at least one card for every book in the library. Usually there were more, as a typical library would have each item in the collection catalogued by author, title and subject, meaning three cards for each item. As we said, for a small library this might be up to ten thousand items. For a large library this could easily be a few million items. So even just the catalogue for a large library could look like this:

Dozens of aisles, each containing hundreds of drawers, each containing hundreds of cards, all meticulously created, filed and maintained by hand. And that was before you got to the items themselves!

Other organisations had catalogues too

If you were a law firm, you would have a large library with all the relevant trials in your jurisdiction, which would be used by attorneys and paralegals when preparing cases for court:

There is no way you’re finding anything in this lot without a catalogue! This example is from a New York law firm who threw out most of their older books when they moved offices in 2014.

If you were a retail company, you would keep records of every shipment of goods that came in, records of stock levels, and records of every sale: what, when and to whom. A retailer with lots of items might have a catalogue that customers could look through when working out what to buy.